Was Einstein noch nicht wusste

Forscherteam bestimmt erstmals absolute Dauer des photoelektrischen Effekts

2018-09-19 – Nachrichten aus dem Physik-Department

Wird ein Festkörper mit Röntgenimpulsen bestrahlt, dann lösen sich Elektronen und wandern an die Oberfläche. Doch wie lange dauert das? Dieser Frage ist das internationale Forscherteam um Prof. Reinhard Kienberger vom Lehrstuhl für Laser- und Röntgenphysik an der TUM nachgegangen. Denn bisher konnten nur Richtung und Energie der Elektronen bestimmt werden. Der Weg der Elektronen etwa durch einen Kristall konnte aufgrund seiner winzigen Dimensionen und der extrem kurzen Dauer des Prozesses bis dato nicht beobachtet werden.

Jod-Atome als Stoppuhren eingesetzt

Das internationale Team hat jedoch eine neue Messmethode entwickelt, die es nun erlaubt, die Zeit zwischen der Aufnahme (Absorption) eines Röntgen-Photons und dem Ausströmen (Emission) eines Elektrons zu bestimmen. Dazu „klebten“ die Physiker einzelne Jod-Atome auf einen Wolframkristall und bestrahlten ihn mit Röntgenblitzen, die den Photoeffekt starteten. Da die Jod-Atome extrem schnell auf einfallendes Röntgenlicht reagieren, dienen sie als Licht- und Elektronen-Stoppuhren.

Um die Präzision der Messung zu erhöhen, wurden diese Stoppuhren dann in einem weiteren Experiment mithilfe einer erst kürzlich entwickelten absoluten Referenz geeicht (siehe zweite Publikation unten). „Dies ermöglicht, das Austreten der Photoelektronen aus einem Kristall mit einer Genauigkeit von wenigen Attosekunden zu stoppen“, sagt Reinhard Kienberger. Eine Attosekunde ist ein Milliardstel einer milliardstel Sekunde. Die Messung zeigt, dass Photoelektronen aus dem Wolframkristall in rund 40 Attosekunden erzeugt werden können – etwa doppelt so schnell wie erwartet. Das liegt daran, dass mit Licht bestimmter Farben hauptsächlich die Atome in der obersten Schicht des Wolframkristalls wechselwirkten.

Ein weiterer interessanter Effekt konnte mit dem Experiment beobachtet werden: Noch schneller werden Elektronen aus Atomen auf der Oberfläche eines Kristalls gelöst. Nach der Bestrahlung mit Röntgenlicht gaben sie ohne messbare Verzögerung direkt Elektronen frei. Dies könnte für die Herstellung von besonders schnellen Photokathoden für eine Anwendung in Freie-Elektronen-Laser interessant sein, urteilen die TUM-Wissenschaftler, da sie nun wissen, wie sie die Photon-Elektron-Umwandlung beschleunigen oder manipulieren können.

Mit der neuen Methode kann außerdem das Verhalten von komplizierten Molekülen auf Oberflächen untersucht werden – ein vielversprechender Ansatz etwa um neuartige Solarzellen zu entwickeln. Denn mit dem Wissen über die bislang unbekannten photochemischen Prozesse können technische Anwendungen viel besser optimiert werden.

Weitere Informationen

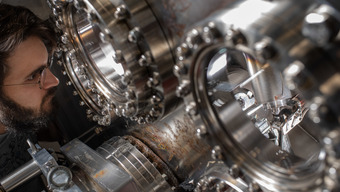

Die Attosekunden-Beamline mit Ultrahochvakuum-Kammer kann am Tag der offenen Tür der TUM besichtigt werden. Tauchen Sie am Samstag, den 13.10.2018 von 11:00 bis 15:00 Uhr ein in die Welt der Attosekunden und besuchen Sie weitere Veranstaltungen des Physik-Departments und der TUM!

Veröffentlichungen

Absolute Timing of the Photoelectric Effect

Attosecond correlation dynamics

Verwandte Meldungen

- Die Attosekunden-Stoppuhr – 2018-06-28

- Auf dem Weg zur Terahertz-Elektronik – 2018-06-26

- Professor Reinhard Kienberger wird Universitätsrat der TU Graz – 2018-03-21

- Eine Billiardstel-Sekunde in Zeitlupe – 2018-02-20

- Erste absolute Bestimmung des Zeitpunktes einer Photoionisation – 2016-11-08