Optische Pinzette enthüllt ein Geheimnis der Muskelkraft

Was das Herz im Innersten zusammenhält

2017-01-24 – Nachrichten aus dem Physik-Department

Der menschliche Körper ist eine Dauerbaustelle: Ständig werden Proteine abgebaut und durch neue ersetzt. Doch dieser stete Umbau beeinträchtigt nicht die Funktion. Das Herz schlägt weiter, die Atmung bleibt nicht stehen, auf unsere Augen und Ohren können wir uns jederzeit verlassen.

Wie es dem Körper gelingt, die Proteinstränge im Muskel zusammenzuhalten, selbst wenn einzelne Bausteine ersetzt werden, beschäftigt Prof. Matthias Rief seit Jahren. „Es muss Kräfte geben, die die einzelnen Ketten, die Filamente, stabilisieren, sonst würde der Muskel auseinanderfallen. Doch ist es bisher nicht gelungen, die Ursache dieser Kräfte aufzuspüren“, berichtet der Inhaber des Lehrstuhls für Biophysik an der TU München. Zusammen mit seinem Team hat er jetzt das Geheimnis des Zusammenhalts der Muskeln entschlüsselt.

Eine optische Pinzette entschlüsselt die Bindungskräfte

Zwei Proteine sind demnach verantwortlich dafür, dass sich Muskeln dehnen lassen ohne auseinander zu fallen: eines davon ist das Titin, das längste Eiweiß des menschlichen Körpers, das andere ist ?-Actinin, das über die Fähigkeit verfügt, das Titin im Muskelgewebe zu verankern.

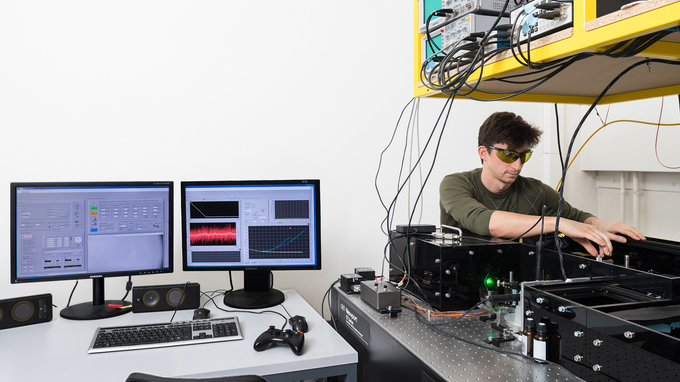

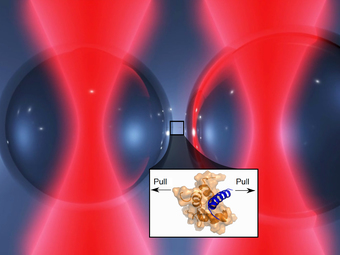

Das Wechselspiel zwischen diesen Proteinen konnten die TUM-Forscher mit Hilfe eines eigens dafür entwickelten Apparats, studieren: Die „optische Pinzette“ füllt einen 20 Quadratmeter großen Raum im Keller des Instituts. Da gibt es Laserquellen, Optiken, Kameras, Bildschirme. Kernstück der Anlage ist eine mit Flüssigkeit gefüllte Messkammer mit kleinen Glaskügelchen, an deren Oberflächen die Proteine Tinin und α-Actinin haften. Zwei Laserstrahlen, welche die Messzelle durchdringen, fangen jeweils ein Kügelchen ein und halten es fest.

Ein Netzwerk spendet Kraft

„Mit Hilfe der Laserstrahlen, können wir die Kügelchen zunächst soweit zusammenbringen, dass sich die beiden Proteine vernetzten“, erklärt Marco Grison, der in seiner Promotionsarbeit die Bindung zwischen den Muskelbausteinen erforscht. „Im zweiten Schritt vergrößern wir den Abstand zwischen den Laserstrahlen und damit auch der Kügelchen, bis die maximale Dehnung der Proteine erreicht ist. Aus diesem Abstand lässt sich dann die Bindungskraft zwischen dem Titin und dem α-Actinin errechnen.“

Fünf Pico Newton hält die Proteinverbindung aus – das entspricht der Gewichtskraft einer Billionstel Tafel Schokolade. „Dieses Ergebnis hat uns sehr überrascht“, erinnert sich Rief. „Derart geringe Kräfte können einen Muskel eigentlich nicht dauerhaft zusammenhalten.“

Und doch ist die Protein-Verbindung der Schlüssel zum Verständnis: Im Muskel wird jeder Titin-Strang von bis zu sieben α-Actinin-Proteinen gehalten. Das haben die Strukturbiologen an der Universität Wien, mit denen die Münchner Forscher zusammenarbeiten, festgestellt. Damit erhöht sich die Kraft um das Siebenfache. Genug, um das Herz schlagen zu lassen, und sogar noch nebenbei – sozusagen bei laufendem Betrieb – einzelne Molekülketten abzubauen und durch neue zu ersetzen.

Reparaturen während des laufenden Betriebs

„In der Summe reichen die Bindungen aus, um den Muskel zu stabilisieren“, erläutert Rief. „Das Protein-Netzwerk ist dabei nicht nur stabil, sondern auch hochdynamisch. Unsere Messungen zeigen, dass sich die Proteine lösen, wenn man sie auseinander zieht. Sobald aber die Dehnung nachlässt, finden sie wieder zueinander.“ Diese Affinität der Eiweißmoleküle zueinander garantiere, dass der Muskel nicht reiße, sondern nach einer Dehnung wieder in seien ursprüngliche Form annehme.

Die enge Verbindung zwischen den Proteinen ist dabei nicht auf das Herz beschränkt. Die Interaktion zwischen Titin und α-Actinin stabilisiert alle Muskeln, die gedehnt werden – gleichgültig ob beim Atmen, Gehen, Greifen oder Lachen.

Grundlagenforschung für die Medizin der Zukunft

Eines Tages könnten auch Patienten von den Ergebnissen profitieren: „Die Grundlagenforschung schafft hier die Basis für ein Verständnis von genetisch bedingten Krankheiten wie Muskeldystrophe und Herzinsuffizienz“, resümiert Rief.“ Das kann Mediziner und Pharmakologen helfen, neue Therapien zu entwickeln.“

Die Arbeiten wurden unterstützt mit Mitteln der EU (Marie Curie Initial Training Network), der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR 1352, Exzellenzcluster Nanosystems Initiative Munich, NIM und Center for Integrated Protein Science Munich, CIPSM), des österreichischen Wissenschaftsfonds und des österreichischen Ministeriums für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Wirtschaft (Center for Optimized Structural Studies, Programm „Laura Bassi Centres of Expertise“).

- Redaktion

- Dr. Andreas Battenberg, Dr. Johannes Wiedersich

Veröffentlichung

Verwandte Meldungen

- Kräftemessen im Erbgutmolekül – 2016-09-12

- “Streckbank” für winzige Moleküle – 2011-10-28